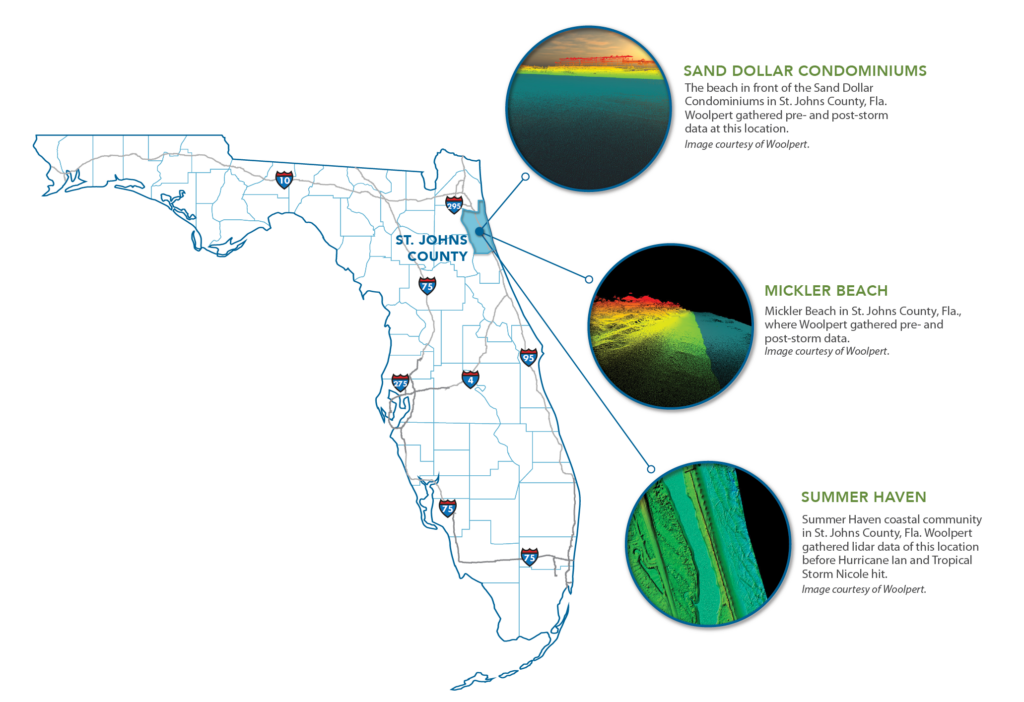

The three sites discussed in this article are all located along the shore of St. Johns Country, on Florida’s Atlantic coast.

Editor’s note:

For additional discussion with Volkan and Rick, listen to the following podcast:

In 2019, Woolpert suggested a novel concept to officials in St. Johns County, Florida: use lidar technology to acquire coastal elevation data before and after hurricanes to help the county monitor beach erosion and support dune maintenance. The county agreed to the proposition, understanding the potential future value of the effort. However, it wasn’t until 2022 that this value was realized after Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole barreled through St. Johns County.

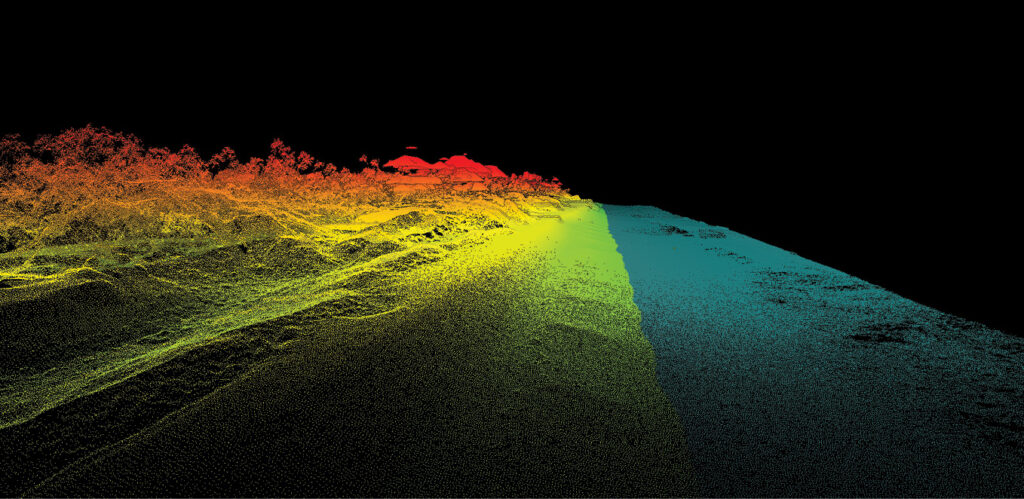

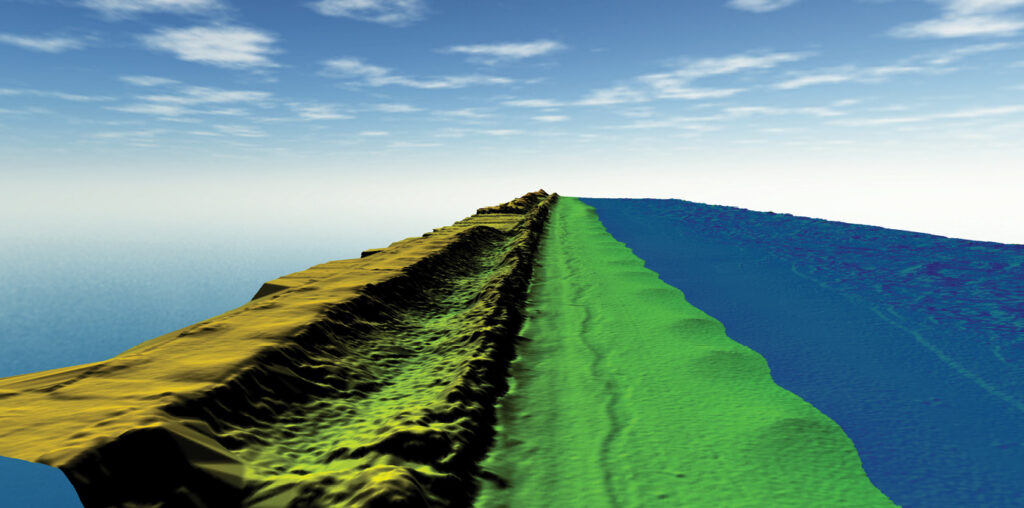

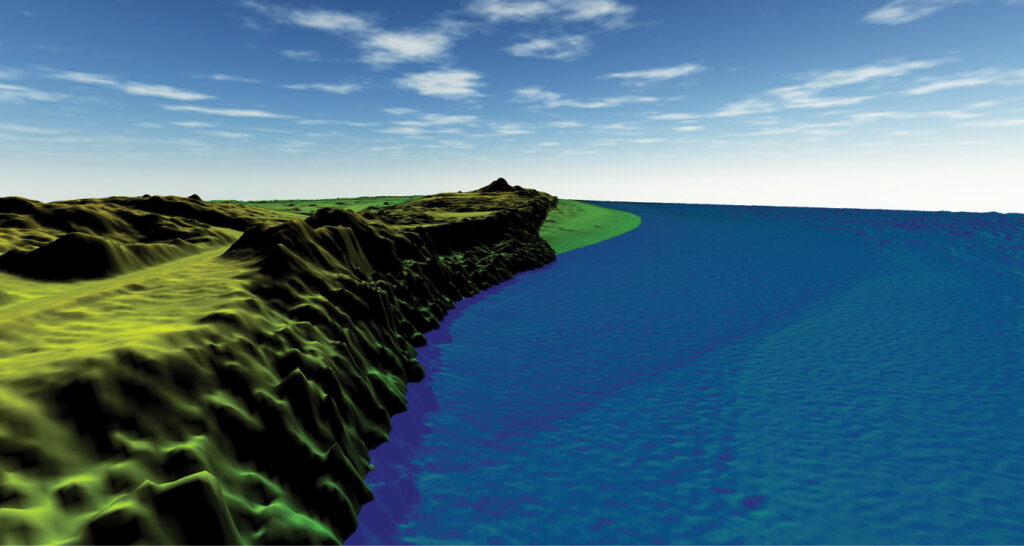

This oblique image of a ground DEM showcases what Mickler Beach in St. Johns County, Florida, looked like before Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole hit. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

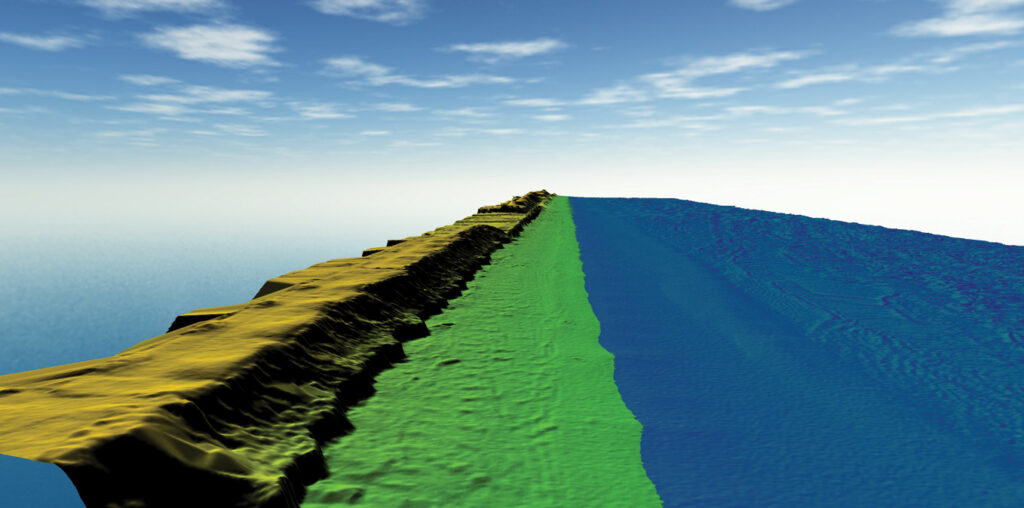

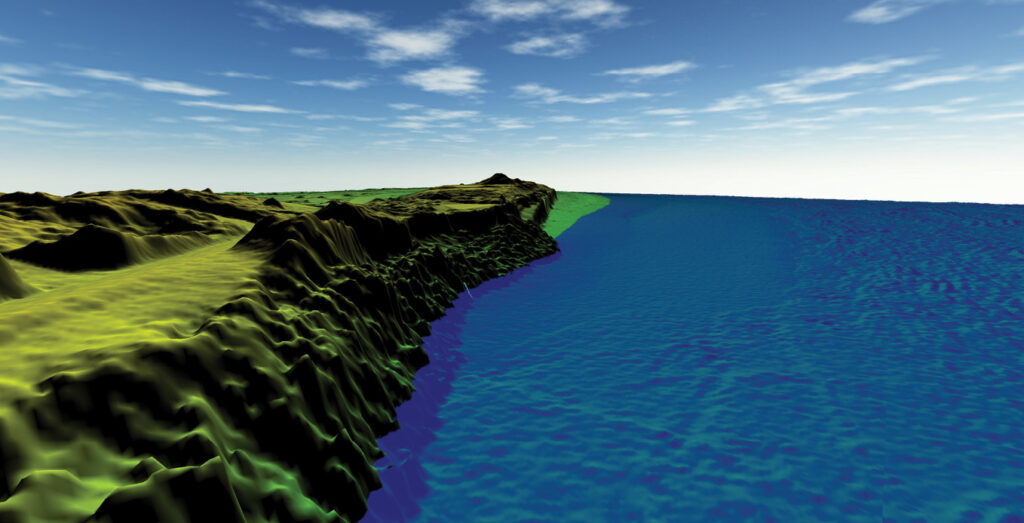

A significant amount of sand was washed away from Mickler Beach in St. Johns County, Florida, after Hurricane Ian tore through the community. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

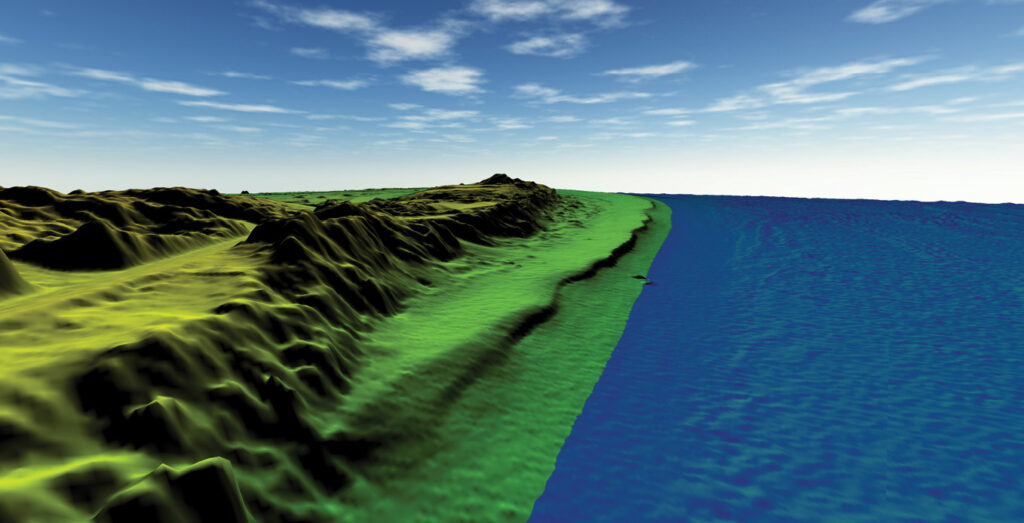

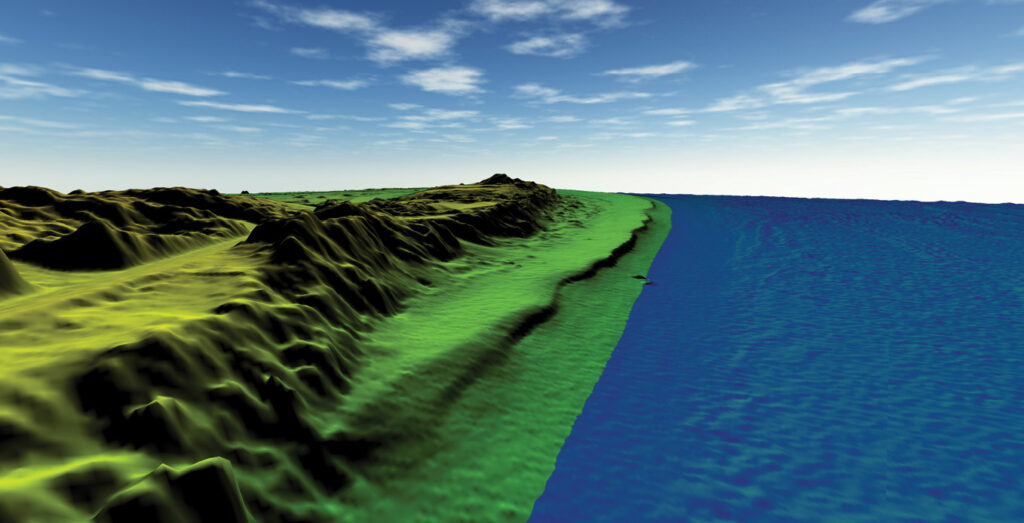

Once Tropical Storm Nicole passed through St. Johns County, Florida, Woolpert used an oblique view of a colorized, 1-foot-resolution ground DEM to highlight the changes to Mickler Beach. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

Upon making landfall on mainland Florida on September 28, 2022, Hurricane Ian hit St. Johns County, causing erosion, outages, downed power lines and trees, and significant flooding1 in downtown St. Augustine, Hastings, Summer Haven, Matanzas Inlet, and Flagler Estates. On November 9, 2022—just six weeks later—Tropical Storm Nicole raged across St. Johns County, breaking and flooding parts of the Coastal Highway2 and causing devastating beach erosion. Despite this swath of destruction, the pre- and post-hurricane elevation data acquired by Woolpert supported a fast and comprehensive emergency response from St. Johns County.

A clear reason despite unclear conditions

In anticipation of Hurricane Ian’s arrival, Woolpert flew lidar on September 23, 2022, between the Duval-St. Johns and Flagler-St. Johns boundaries, extending from the Atlantic Ocean shoreline to three varying distances landward of the waterline. After the first extreme weather event, Woolpert flew again on October 11, and began processing the data to assess the damage Hurricane Ian had caused to the St. Johns County coastline. Before the firm could provide the deliverables to officials, however, Tropical Storm Nicole hit, requiring Woolpert to fly lidar for a third time on November 18.

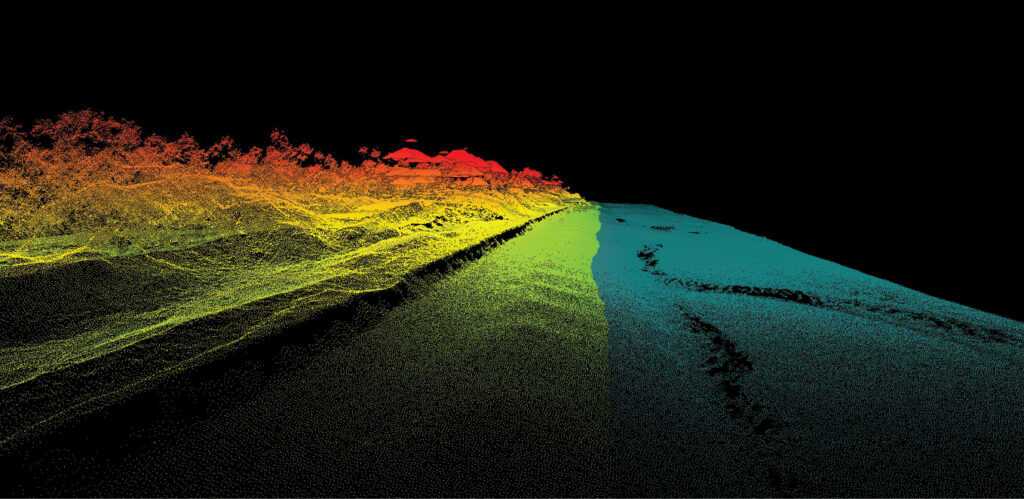

An oblique view of a colorized, 1-foot-resolution ground DEM, this image shows the beach in front of the Sand Dollar Condominiums in St. Johns County, Florida, before Hurricane Ian. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

This oblique visual depicts how much beach was lost in front of the Sand Dollar Condominiums after Hurricane Ian hit St. Johns County, Florida. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

Tropical Storm Nicole came several weeks after Hurricane Ian, eroding more beach in front of the Sand Dollar Condominiums in St. Johns County, Florida. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

“In 2022, we had the opportunity to gather pre- and post-hurricane elevation data for the first time since the program’s inception,” said Michael Meiser, Woolpert vice president. “In previous years, St. Johns County didn’t have hurricane events of this magnitude, so there wasn’t enough to merit data acquisition. But the 2022 storms provided multiple reasons to investigate and evaluate what happened to the St. Johns County coastline.”

While the justification was there, one challenge still existed: accurately timing the data collection. This step was imperative for developing a complete picture of the destruction caused by each storm. Gathering the data within a week of each event was ideal but mobilizing aircraft so quickly can be quite challenging.

“We knew that other people would try to fly in that airspace, especially for emergency response,” said Sam Moffat, Woolpert geospatial program director. “Coordinating the airspace and collecting lidar data soon after Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole required significant effort. After strategizing with St. Johns County officials to get a thumbs up to gather post-storm elevation data, we had to navigate tidal and weather patterns as well as obtain airspace approval.”

Once the airspace was secured, the next step was acquiring high-quality data despite dreary, rainy, and cloudy conditions caused by remnants of the extreme weather events. For the best chance to gather consistent data, Woolpert flew lidar within approximately one hour on either side of astronomical low tide in the adjacent Atlantic Ocean. The data acquisition took place when the atmosphere was primarily clear of poor conditions and other phenomena that would hinder or negatively impact the success of the data collection effort. Additionally, Woolpert flew at an altitude of approximately 2400 feet above mean terrain.

“At this altitude, we could fly under the clouds that are so prevalent along the eastern coast of Florida during the summer and fall,” Moffat explained. “This altitude also produced a point cloud with more than 20 points per square meter.”

This strategy resulted in an extremely dense and precise surface model with a vertical accuracy of approximately 5 centimeters, enabling Woolpert to provide multiple deliverables, including ground-derived digital elevation models with 1-foot resolution and 8-bit grayscale intensity images, which vividly portrayed the damage to St. Johns County’s beach areas. These portrayals showed a level of devastation the coastal county had rarely seen.

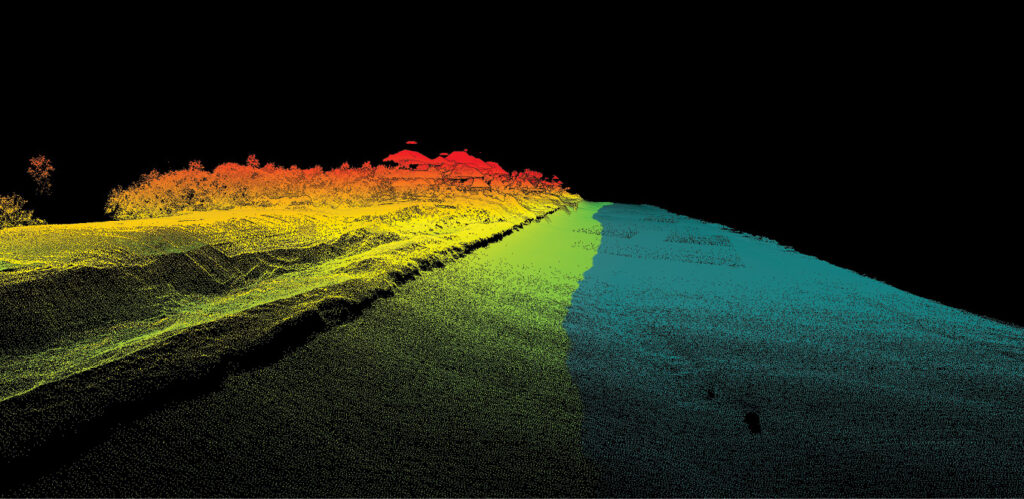

“On average, Hurricane Ian wiped away approximately 50 feet of beach and Tropical Storm Nicole eroded around 60 feet,” Meiser said. “Both storms hit some places in the county harder than others. For example, in Summer Haven, these natural disasters moved the community’s entire beach west across an intercoastal waterway.”

Forward-thinking approach to response and resilience

Rebuilding damaged areas along the St. Johns County coastline was essential after Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole. Tourism is the county’s primary economic engine, benefiting businesses, investors, and residents, and is continuously growing. According to Downs & St. Germain Research3 over 10 years ago, St. Johns County generated $712 million annually from visitors; between July 2021 and June 2022, that figure jumped to $2.4 billion. This revenue supports jobs, businesses, and investors as well as programs and attractions that visitors and residents alike enjoy.

A colorized image of a 1-foot-resolution ground DEM, this visual depicts Old A1A Beach Access Point in Summer Haven, a coastal community in St. Johns County, Florida. The imagery shows what the access point looked like before Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

Summer Haven in St. Johns County, Florida, was hit particularly hard by Hurricane Ian. This colorized image shows how the extreme weather event damaged the Old A1A Beach Access Point. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

This colorized image of a 1-foot-resolution DEM model illustrates the changes to the Old A1A Beach Access Point after Tropical Storm Nicole passed through. Image courtesy of Woolpert.

Without tourism, the St. Johns County economy stands to take a significant hit. Preserving tourist revenue was a primary reason that officials used the pre- and post-hurricane elevation data to support and enhance their response and resilience efforts. It’s also why the county maintains the coastal management team that spearheaded the dataset implementation.

“Our coastal management team is a well-rounded group that’s dedicated solely to coastal management—it’s what we think about all the time,” said Stephen Hammond, St. Johns County coastal environment project manager. “The county recognizes that the beaches are extremely important, and we need to know what’s going on with them. Data is critical to help to determine that.”

Once the coastal management department saw the destruction Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole inflicted on the county’s beaches, they used the data to develop a multi-pronged approach. One of the department’s first steps was to alert county leaders and the general public to the significant storm-related damage. This visibility promoted cooperation in designating resources to rehabilitate the areas needing the most attention.

“We were able to show the public which areas of the coastline were most impacted by the storms. While everyone could see the damage with their own eyes, we came up with damage estimates based on actual data. It was really important to put numbers behind the visuals for our leaders to share how severely our coastline was hit with different organizations and levels of government.”

Along with providing impact estimates to the public and county leaders, the coastal management department showcased pre- and post-event DEMs using Woolpert’s Smartview Connect™, a web-based tool offering visual representations of the destruction to St. Johns County’s coastline.

“A picture is worth 1000 words,” said Ben Beckman, geospatial team leader at Woolpert. “Using Smartview Connect, the department could show residents and leaders the extent to which the beaches were wiped away after Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole. That imagery is a great resource to provide to those who aren’t familiar with lidar technology.”

The coastal management department also used the data to determine how much sand was lost in the upper, dry-beach portion of the dune system and what remained behind the elevations of the existing dunes, which were there to protect the upland infrastructure.

“We used this information and worked with FEMA and our consultants to determine the eligibility for a FEMA category B berm,” Hammond explained. “This type of project is considered emergency repair of the dune system. Rather than rebuilding all the sand the storms took away, we were enhancing what was left behind on large, impacted sections of the beach. We had to show the elevation of the remaining dunes to determine if a section was eligible for this type of project, so having the pre- and post-storm elevation datasets available was critical. An additional criterion for eligibility is starting construction within six months of the storm declaration, which is extremely hard to do. However, having the datasets available quickly supported the fast analysis needed to meet this tight timeline.”

The coastal management department also sent the data to its consultants and partners working on varied projects across the community. With 42 miles of coastline, St. Johns County had 10 active projects on different sections of the beach. Two of the projects—the South Ponte Vedra and Vilano Beach project and the St. Augustine Beach project—were with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“These two Corps projects were emergency renourishment initiatives,” Hammond said. “Before these storms hit, we were planning to place around 2,000,000 cubic yards of sand on those project sites. After Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole passed, we worked with the Corps to reanalyze the conditions on the beach and project areas, using the pre- and post-storm elevation data to update that number. We actually increased the amount of sand we needed to bring into the project areas because the storms washed away so much of the existing sand.”

Additionally, the department used the datasets to update various project bid plans. Without the post-storm data, potential bidders would not have had an accurate picture of project areas. When the department delivered the updated data to its consultants, they paired it with new exhibit bid documents to accurately showcase how significantly the project sites had changed after each storm. The timely data served to ensure bidders were aware of the new reality facing the projects and that they had the most current information to complete them successfully.

Parting the waves to receiving long-term federal funding

For St. Johns County, the pre- and post-storm elevation data has value beyond engaging the public and moving current or reactive response and resilience projects through the pipeline. This annual dataset will also be beneficial in attracting funding for ongoing efforts.

“We’re working toward a coastal management plan that will hopefully set us up for the next 50 years and advise on future project needs along the coastline,” Hammond explained. “The coastal management plan is a long-term initiative that will include tracking what’s happening on the beach and the areas of erosion so that we know when to start planning projects and seeking funding. This data will be extremely helpful in supporting that effort.”

Regular pre- and post-storm elevation data will improve St. Johns County’s chances of success in securing funding. Similar to other coastal communities, St. Johns County has many engineered projects: once the coastal management department constructs a shoreline project, the beach is categorized as engineered. Engineered beaches impacted by storms are eligible for additional funding, so possessing accurate pre- and post-storm elevation data gives the department an advantage with respect to securing money when projects are needed.

When explaining how pivotal the datasets are in securing funding, Hammond referenced a recent project for which the county acquired funding as a result of Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole. “We just did a local- and state-funded project in South Ponte Vedra Beach, where we constructed a full beach restoration of the dunes and berm—but it washed away in about six months due to the impacts of Hurricane Ian and Tropical Storm Nicole,” Hammond said. “We were able to use the lidar data and additional underwater bathymetric data to determine how much sand was lost. FEMA will help reconstruct the project with Category G funding. If we didn’t have a project there already or the lidar dataset, there wouldn’t be funding sources like this to help us, and we would have to fund it either locally or hope the state sends some money our way.”

The coastal management department also wants to use the data regularly to discover areas that are eligible for Corps projects. According to Hammond, these projects are the “gold standard” because they are funded by a cost-sharing partnership between the Corps and the county. This arrangement ensures that major storm damage to the county coastline will be mitigated by Corps funding, at least in part.

“Working with the Corps is an amazing opportunity,” Hammond says. “If it’s a non-federal project, the county must cover the cost of rebuilding after a storm. But if a declared storm impacts a Corps project and we have data supporting the need for restoration of the project, the federal government will pay for 100% of it.”

When commenting on all the benefits St. Johns County has seen from the data, Jeff Lovin, senior vice president and senior strategist at Woolpert said, “We are extremely grateful for the nearly 30-year partnership with St. Johns County and that most recently we were able to provide them with valuable pre- and post-storm data to aid in their recovery. As the frequency and intensity of storms battering our coastlines increase, more coastal communities in Florida and throughout the nation should look at similar programs.”

Coastal communities need to prepare

Hurricanes have increased in intensity over the past four decades, leading to more destruction. With seas becoming warmer, the likelihood of a hurricane turning into a category three or higher storm, with winds traveling at more than 110 miles an hour, has increased by 8% per decade since 1979. A 2023 report by First Street Foundation even suggests that, in the decades ahead, stronger storms will impact communities deeper inland, potentially damaging 13 million properties that are typically unaffected4.

While coastal communities can’t negate the effects of natural disasters, they can put themselves in a position to respond quickly to hasten their recovery. By flying lidar over shorelines before and after hurricanes, coastal communities can pinpoint their beach areas needing the most attention and then effectively design solutions and implement plans.

“Having the before and after elevation data will really help counties make accurate and more scientific decisions on the next steps for their coastlines,” Hammond said. “In the long term, counties can be more proactive than reactive to storms. Right now, everything going on is reactive, so putting a long-term monitoring program like this together can really help counties develop a proactive approach.”

Additionally, counties can use the data to help secure federal funding for resilience and response initiatives. Extreme weather events have significant economic impacts on communities, and Rick Spinrad, administrator at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), told USA Today that since January 2023, “There have been a record-setting seven disasters that have totaled a billion dollars or more each in damages.”5

To help coastal communities become more resilient, the U.S. Department of Commerce recently announced a $2.6 billion grant, which includes $575 million for regional challenge grants provided by NOAA. Securing these grants will be easier for coastal communities that have data depicting their shoreline damage.

With secured funding, coastal communities can rehabilitate damaged beach areas to keep residents, businesses, and investors happy and, more importantly, maintain their biggest economic driver—tourism. Recreation and tourism in shore-adjacent communities in the U.S. account for $143 billion in gross domestic product6. If those coastal communities can’t rehabilitate their beaches and entertainment districts after hurricane season, the number of visitors will inevitably decline. Less tourism means less money.

“Beaches are what draw people every year to many coastal communities, especially in Florida,” Moffat said. “They are the engine for Florida’s economy and all of the coastal communities in the state. Even if you aren’t overly concerned with the general health of the ecosystem, the health of these beaches is important for the economy and attracting tourist dollars. If coastal communities use lidar to gather pre- and post-storm elevation data, their engineering groups can use the data for all kinds of analysis, planning, and mitigation procedures to keep their beaches and economies strong.”

3 co.st-johns.fl.us/tdc/media/Florida-%20Historic-Coast-July-2021-June-2022-Economic-Impact-Report.pdf