Digital twin helps design new neighborhood without spoiling ballpark views

Principal Park is a great place to view the historic past of Des Moines. As the homefield for the Iowa Cubs, the city’s Triple-A Minor League Baseball team, the stadium affords a picturesque view of the Iowa State Capitol, beyond center field. Iowans are justifiably proud of their statehouse. The building, constructed in a Renaissance style and topped by a gold dome, is a fixture on lists[1] of the nation’s most beautiful state capitols.

But what about the future of Des Moines? Until recently, it seemed like a proposed reinvigoration of a neighborhood on the far riverbank could threaten that ballpark view. Using a cutting-edge geographic tool, city officials found a way to green-light the project while preserving the view.

The capability for such spatial analysis is arriving at a crucial time as shifting demographic patterns and spiraling living costs on the coasts and Sun Belt are resulting in a resurgence of interest in the Midwest. The population of the Des Moines region increased by 15 percent[2] between 2010 and 2018, making it the Midwest’s fastest-growing metro area. In 2014, The Atlantic declared moving to Des Moines “the most hipster thing possible[3].”

A new neighborhood vision

In past eras, this might have been a boon to Des Moines suburbs. Today, more people want an urban experience. What better way to provide that than by reinvigorating a well-preserved but neglected reminder of the city’s bygone urbanity? Enter the revitalization of Des Moines’s East Village, which stretches from the statehouse to the riverbank, a longstanding project just waiting to be revived.

“You could tell that the neighborhood had that cool, urban vibe that a lot of people seek out,” said Ryan Moffatt, City of Des Moines economic development coordinator. “It was the next natural path of urban development. It’s adjacent to downtown, it’s on the city’s waterfront, and it’s near a recreational trail system. Plus, it’s got a great view of the downtown skyline.”

The southern part of the neighborhood also lies between the statehouse and Principal Park, which raised the specter of blocked views from the ballpark. In 2017, the city began to take a closer look at a 2002 City Council agreement that capped building heights at 75 feet. A vision to expand the East Village as a “walkable, dense mixed-use neighborhood began to emerge,” said Michael Ludwig, deputy director of Des Moines’s development services department, “with green architecture and a focus on sustainability.”

JSC Properties, a local developer, floated a proposal to create that neighborhood, transforming 40 acres of the East Village into what would be called the Market District. The plans were embryonic, but they would almost certainly include buildings that rose above 75 feet.

JSC estimated that the total cost of developing the Market District would be around $750 million. That figure – about 10 times as much (in inflation-adjusted dollars) as the cost of the capitol’s construction in the 19th century – represented a huge investment in the city’s future, but was it worth besmirching the fans’ vision of Des Moines’s shining beacon on a hill?

The true view

The situation was not necessarily intractable. Although the 75-foot rule was legally binding, it was merely the best guess at the time by planners who did not have the benefit of today’s technology for urban planning and economic development.

More specifically, modern geographic information system (GIS) software with reality capture, imagery analysis, and advanced visualization, offered a way forward.

“The developers were talking about space, but they couldn’t visualize it,” said Aaron Greiner, City of Des Moines GIS manager. The city was considering hiring a consultancy, but Greiner proposed a different option.

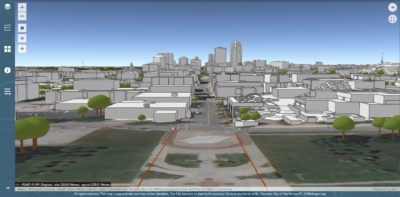

For $20,000—a fraction of the cost of using outside consultants—the city could hire an aerial imagery company to fly over the area and take lidar readings. Greiner’s office could then use the lidar data and GIS software to build a 3D basemap.

Greiner was describing the creation of a “digital twin,” a virtual representation of the processes, relationships, and behaviors of a real-world system. The concept originated in manufacturing to keep detailed records of factories and assembly lines. More recently, digital twins have been used to analyze geographies in real time.

For city planners, a digital twin functions as an authoritative crystal ball. The idea is not to create a record of the way things are (or were), but of how they might be if certain changes are made.

Digital Des Moines

Using the 3D model, planners were able to pinpoint the area that needed lower height restrictions in order to preserve the view of the capitol from home plate.

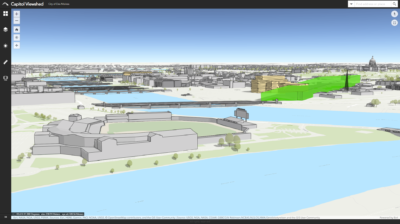

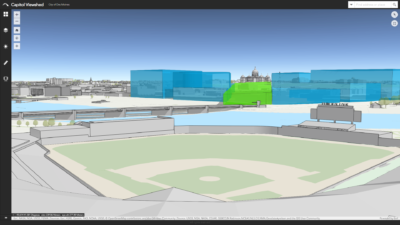

Erik Brawner, a GIS analyst for the City of Des Moines, recently demonstrated how the digital twin has helped make the Market District possible. After calling up the 3D map on a monitor, he “flew” into Principal Park, showing the perspective from just behind home plate, the spot where a catcher crouches. Out in the distance, the statehouse was visible on the hill.

Brawner pointed out green shading that extended beyond the stadium. “That’s the original viewshed, defined by the original 75-foot rule,” he said.

On the fringes of the green were some blue areas. “That’s the rest of the development area the developer is proposing,” he explained. “So the digital twin is showing the height that buildings could go up to and not create too much of a tunneling effect on the view.”

Working with the digital twin, JSC could collaborate with planners like Ludwig, introducing models of proposed buildings and seeing the visual effect they would have.

“This has blown his mind,” Greiner said of Ludwig, “because in the past, they’d go out and do hand measurements, then put it on graph paper and scale up. They’d spend weeks, if not months, doing calculations.” Now, he said, it was merely a matter of dropping building models into the digital twin and observing how they impact the view.

The Market District and beyond

Last year, JSC and the city used the digital twin to conduct an extensive viewshed analysis, discovering that some buildings could indeed extend above 75 feet without obstructing the view. Using the findings, the city approved[4] a new ordinance in January that codified how the Market District could proceed.

While the other viewsheds have not yet been tested, Ludwig explained, Principal Park offered an important proof of concept. “This was the big one,” he said. “Balancing the desire any city council would have for $750 million in development with the desire to protect aesthetics and the view of the capitol building, this has been an extremely valuable tool,” he added. “If we didn’t have it, they would’ve probably said, ‘Forget about that 20-year-old agreement—we can’t pass this up.’ What this really helped us do was find a happy medium.”

The tool is poised to help Des Moines manage its growth—especially as more people realize that, with remote work increasingly the norm in the post-pandemic world[5], they can work from anywhere. As the Market District evolves with these new arrivals, the 3D basemap that began as a way to preserve a ballpark view will help facilitate the overall development and design.

“When the individual projects come into the area, they’ll give us their building plans in whatever form they have,” Ludwig explained. “We can plug them into the model and see whether they’re projecting through the zoning restriction ceiling, and quickly evaluate them.”

The GIS office plans to make the digital twin available to other city offices. As more data increases the complexity of the tool, these managers will find new uses for it that enhance overall understanding of the area.

“Just this week, I got an email from the parks department, asking if they can use it for shadow modeling, because they’re interested in finding a place for a community garden that would have adequate sunlight,” Greiner said. “We haven’t quite tackled that one yet, but we will.”

Learn more about how planners use GIS for urban and community planning[6] initiatives and economic development[7].

This article originally appeared on Esri Blog[8].

Christine Ma is the Urban Planning Practice Lead at Esri Professional Services, helping planners from local governments, regional agencies, and AEC firms leverage geospatial technology in planning workflows. Christine joined Esri in 2015 and now oversees the urban planning projects within Esri’s Built Environment Department.

Christine Ma is the Urban Planning Practice Lead at Esri Professional Services, helping planners from local governments, regional agencies, and AEC firms leverage geospatial technology in planning workflows. Christine joined Esri in 2015 and now oversees the urban planning projects within Esri’s Built Environment Department.

Take a bite out of blight

The East Village isn’t the only part of Des Moines experiencing a renewal. Across the city, neighborhoods are undergoing a transformation as new arrivals pour into the city.

Two years ago, the city launched its Blitz On Blight program to identify properties that contain buildings declared to be a public nuisance. These are structures that have fallen into disrepair, and whose owners have been ordered to make certain improvements. If they fail to do so, and cannot work out a rehab agreement with the city, the buildings are demolished.

The issue of blight is often politically charged. City officials can be put on the defensive when residents ask them why certain properties are considered blighted.

To promote transparency, the Des Moines program includes an interactive data dashboard and map[9] that lets the public see exactly which properties are targeted. Clicking on an icon representing a property brings up information about why the property merits the distinction, as well as the current stage of the process.

Because the process is an arduous one—Iowa has one of the longest foreclosure periods of any state—the map provides Des Moines residents with a way to assess the status of individual properties and the project as a whole. “We can now provide the public a firsthand account of what’s happening in their neighborhood and the progress being made,” said SuAnn Donovan, the city’s assistant director of neighborhood services.

[4] https://www.dsm.city/news_detail_T2_R321.php

[6] https://www.esri.com/en-us/industries/urban-community-planning/overview

[7] https://www.esri.com/en-us/industries/needs/economic-development

[8] https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/blog/

[9] https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/991aeb2af53343f68d73476a1f56a500