Education and professional development in the geospatial community1

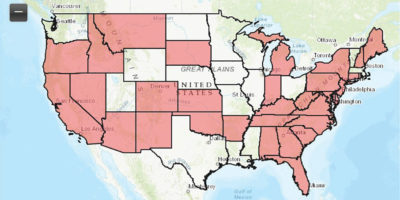

Figure 1: State licensure map—authoritative imagery; from the ASPRS “Licensure Maps and Regulations” website.

It is a challenge in the current environment of fast-paced technological advancement to ensure that those providing products and services are both capable and qualified to fulfill the needs of clients and customers. How do users of current and future technologies choose providers? How do they know that the product or service they are receiving will have a reasonable level of correctness and completeness? Licensure and certification have provided traditional paths for demonstrating knowledge and technical proficiency. “Certification” has historically been utilized to evaluate and ensure technical competence, while “licensure” has traditionally been the mandate of legislation (at both the state and federal levels) premised by the need to “protect the public health, safety and welfare.” Traditional requirements to become licensed include a combination of a defined level of formal education, experience (e.g., time), demonstrated competency in practice (e.g., examples of past work), references from other licensed persons and validation by testing.

Licensing has long been a requirement for doctors, lawyers, engineers and land surveyors. As technologies have advanced, many states have realized the need to license photogrammetrists, providers of a variety of geospatial information (e.g., geographic information systems professionals, or GISPs) and, more recently, those providing lidar data collection and processing services by operating unmanned aerial systems (UASs), such as pilots and/or flight planners. As more states enact legislation relating to existing and new geospatial products and services, it is difficult for practicing professionals, state and national organizations, and the public to keep up with changes to existing rules and regulations and the addition of new rules and regulations. The American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ASPRS), as the leading scientific organization representing the photogrammetry and remote sensing profession, provides a resource to readily access this new and changing information. Figure 1 is part of the “Licensure Maps and Regulations” website2, which gives metadata on state surveying regulations, board website, individual state regulations and composite state regulation document; and state licensure maps for GIS services, lidar and topographic products, georeferenced imagery, and authoritative imagery.

As of this writing, twenty-one (21) states have existing regulations relating to georeferenced imagery products and services; thirty-three (33), relating to authoritative imagery products and services; forty-seven (47), relating to topographic mapping-related products and services (which includes lidar services); and fifteen (15), relating to GIS-related products and services.

A list of the current regulations is just the first step. Every provider of a potentially regulated product or service should be aware of and understand how specific state regulations impact their practice, because each state regulates geospatial products and services differently. Products or services that are regulated in one state may not be regulated the same way (or at all) in another state. For the practicing geospatial professional (whether an engineer, surveyor, photogrammetrist, GISP or UAS pilot), knowledge of an individual area of practice is essential. Knowledge of state, local and possibly even federal regulations is required to properly perform services, provide products, and fulfill contractual requirements for clients.

As mentioned earlier, the geospatial industry is going through rapid changes as advances are made in measurement technologies and capture platforms. The miniaturization of measurement technologies (e.g., imagery and lidar systems), combined with the new and readily available low-cost UASs, has created an unprecedented opportunity for both individuals and firms to get into the business of collecting data to support an ever-expanding variety of geospatial products and services. The field-to-finish (e.g., black box) software solutions supporting these developments enable anyone to provide products that appear to be the same as those that have historically been created utilizing validated photogrammetric methods.

At almost every major geospatial conference in the last few years, the “big” giveaway is a UAS. Does this mean that anyone can use this technology to create and provide services to the public? Various states have proposed or enacted legislation that clearly states otherwise. Over the last few years, regulations have been enacted by over twenty (20) states regarding UAS use3. FAA enacted its Section 333 exemption policies through the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 20124 and in November 2015 published its report5, in which it recommended that all UASs flying within U.S. airspace that have a mass of more than 250 grams (0.55 pounds) be registered with FAA.

The new legislation and rules are examples of how the landscape of certification and licensure is being affected by new technologies. These rapid changes beg the questions as to which geospatial products and services should require certification and which should require licensure. How will the current and future practice of certified and/or licensed professional practice be affected by these changes? The answers to these questions will define the future of all practicing geospatial professionals, whether they are engineers, surveyors, photogrammetrists, GISPs or UAS pilots.

To help facilitate appropriate regulations regarding certification and licensure, the ASPRS Professional Practice Division (PPD)6 proactively engages states to discuss potential legislative changes and assists states by reviewing current and proposed state licensure laws related to geospatial products and services. ASPRS PPD works with individual states to ensure that there is an available licensure path for appropriately educated and experienced professionals. ASPRS PPD also actively engages other national geospatial organizations (URISA, NSPS, MAPPS, etc.) to coordinate efforts of regulation review and interpretation, with the goal of appropriately advising legislative bodies on legislation relating to existing and future geospatial products and services. Additionally, ASPRS has formed its Unmanned Autonomous Systems Division7, the objectives of which include outreach and education, liaising with UAS-interested parties outside the Society, development and promotion of standards and best practices, establishment of calibration and validation sites, and credentialing and certification activities.

While it is in the best interest of every practicing professional to be active in his or her individual national organizations, it is incumbent upon every practicing geospatial professional to stay up to date on the specific rules affecting his or her practice. This combination is the only way to ensure the appropriate implementation of certification and licensing requirements, while also safeguarding the health, safety and welfare of the public in our fast-paced geospatial world.

1 This article is an updated version of a previously published paper: Zoltek, M., 2019. Licensing, certification and new technologies, Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, 85(9): 621-622. doi: 10.14358/PERS.85.9.621. Published here with permission from the American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, www.asprs.org.